National Cybersecurity Strategy. A primer.

TLDR

A national cybersecurity strategy (NCS) is a tool for countries to articulate their overarching vision, high-level objectives, principles, and priorities for cybersecurity. A well-crafted NCS – which differs from plans, policies, and laws – aligns stakeholders, optimises resource allocation, and addresses unique national threats, vulnerabilities, and objectives.

Despite the growth in global adoption of NCSs, guidance on how to craft one remains scarce. The “Guide to Developing a National Cybersecurity Strategy” is one of the few available resources and provides detailed, replicable processes and good practices.

However, pitfalls persist. Common mistakes include treating an NCS as a mere administrative task, limiting stakeholder involvement, or over-outsourcing it creation.

Strategic Foresight can help enhancing NCS's effectiveness. While still limited to mature contexts, its broader use can help make strategies more resilient and forward-looking. At Experirē we are committed to assisting countries in adopting it, and we are also working on introducing NCS performance evaluation metrics, which would further support the forward looking perspective of Strategic Foresight.

The Prime Minister of Qatar presenting the Qatari NCS to the public.

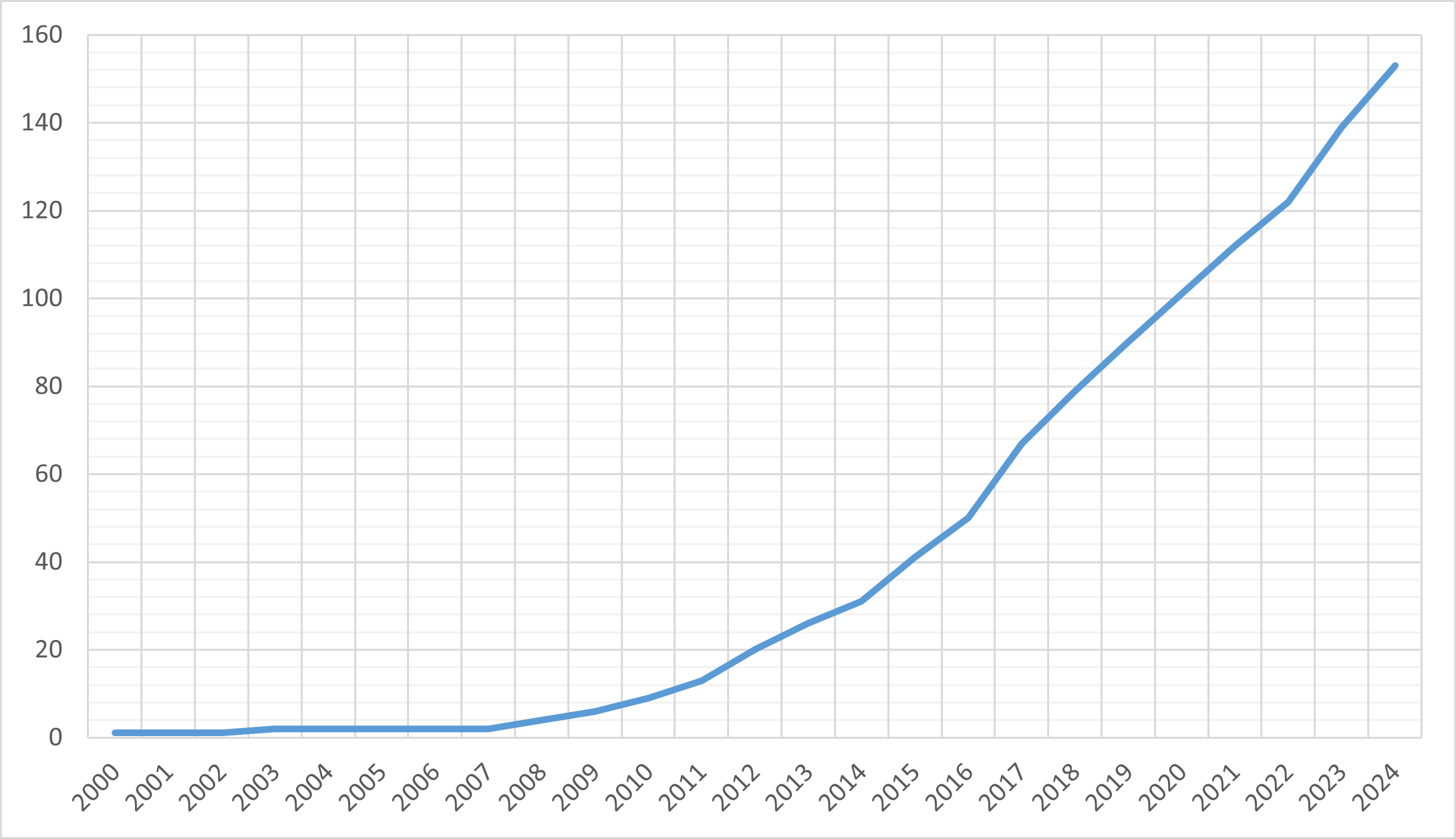

A national cybersecurity strategy (NCS) is a country's formal commitment to securing its cyberspace and digital infrastructure. These first began to appear in the early 2000s, with pioneering work from the United States in 2003. By the end of 2010, a bunch of countries (including Estonia, Australia, the UK, Burkina Faso, and others) followed through and published their strategies. The number continued to grow and experienced an acceleration in the past ten years. Today, more than 150 countries have completed at least their first NCS. This was driven by increasing digitalisation, growth in donor funding for developing nations, and new compliance requirements, such as the European Union's NIS 2 Directive.

However, what is an NCS, and why should anyone care about it? In this piece, we give a brief introduction.

What is a national cybersecurity strategy – and what it is not

Although there is no commonly agreed-upon definition of NCS, we can safely say that it can be defined as the “expression of the vision, high-level objectives, principles, and priorities that guide a country in addressing cybersecurity”. To this definition, it should be added that strategy includes the deliberate and proactive commitment to achieve the identified objectives. It is a rational effort made by policymakers within the context of governing a country.

Sometimes the terms “strategy,” “policy,” and “plan” are used interchangeably. To be exact (without getting pedantic or too academic), they are not the same. To simplify, we could say that a strategy identifies a series of goals to be achieved, a plan outlines a series of actions to achieve those goals, and a policy guides the overall behaviour of the country. Consider the following example:

- Goal (strategy): The country will be ransomware-free.

- Action (plan): Train 100% of country residents to spot phishing attempts 100% of the time.

- Behaviour (policy): Offer the training for free through accredited training centres.

Although they are different things, a strategy without a precise and actionable implementation plan is little more than a "vision document." Thus, even though they should not be confused, these should coexist in the toolbox of policymakers.

Of course, the understanding and use of the three terms above may still vary in different contexts. Therefore, under certain circumstances, it is still somewhat acceptable to use them interchangeably.

A less acceptable (and to be fair, less common) mix-up is to confuse cybersecurity strategy with cybersecurity law. These would typically establish mandatory compliance requirements and corresponding penalties. Let’s apply the distinction to our previous example.

- Goal (strategy): The country will be ransomware-free.

- Action (plan): Train 100% of country residents to spot phishing attempts 100% of the time.

- Behaviour (policy): Offer the training for free through accredited training centres.

- Requirement (law): Every resident of age must take the training.

- Penalty (law): When a resident of age does not take the course, he/she will be fined.

Cybersecurity laws are essential to the country's strategic approach, but they are different from the overall strategy. Not only do they pursue other objectives, but they also require different skillsets to be prepared and enacted.

Why countries need a national cybersecurity strategy

As digital infrastructure becomes increasingly critical to, and embedded in, economies, governance, and everyday life, the associated risks also increase accordingly. These risks necessitate a broad range of initiatives and actions to mitigate, which require diverse stakeholders, skill sets, tools, and budget lines. Such fragmentation speaks volumes about the need to coordinate national effort. This is where an NCS comes into play.

A national cybersecurity strategy provides a unified approach, aligning resources and stakeholders around clearly defined priorities that are identified based on the country’s needs and aspirations. By clearly defining priorities, countries can allocate resources efficiently, avoiding duplication, maximising the return on investment, and targeting gaps, issues, and challenges more effectively.

Furthermore, the process of creating an NCS can act as a platform to facilitate coordination among stakeholders, including governmental agencies, critical infrastructure operators, the private sector, academia, and international partners, helping to break away the siloed approach that still characterises the cybersecurity ecosystems in many countries.

Unfortunately, there are no studies that systematically assess the positive (or negative) net impact of NCSs, and evaluation of this kind remains anecdotal and experience-based rather than data-driven. At Experirē, we are addressing this lack of quantifiability, and we aim to introduce metrics to support policymakers' work soon.

Where should policymakers start the process? Introducing: the NCS Guide

Developing an effective cybersecurity strategy can seem daunting. Strategies must reflect each nation's unique context, taking into account distinct threats, vulnerabilities, and technological environments. Getting this complex equation right is certainly no small feat, and different countries adopt different approaches.

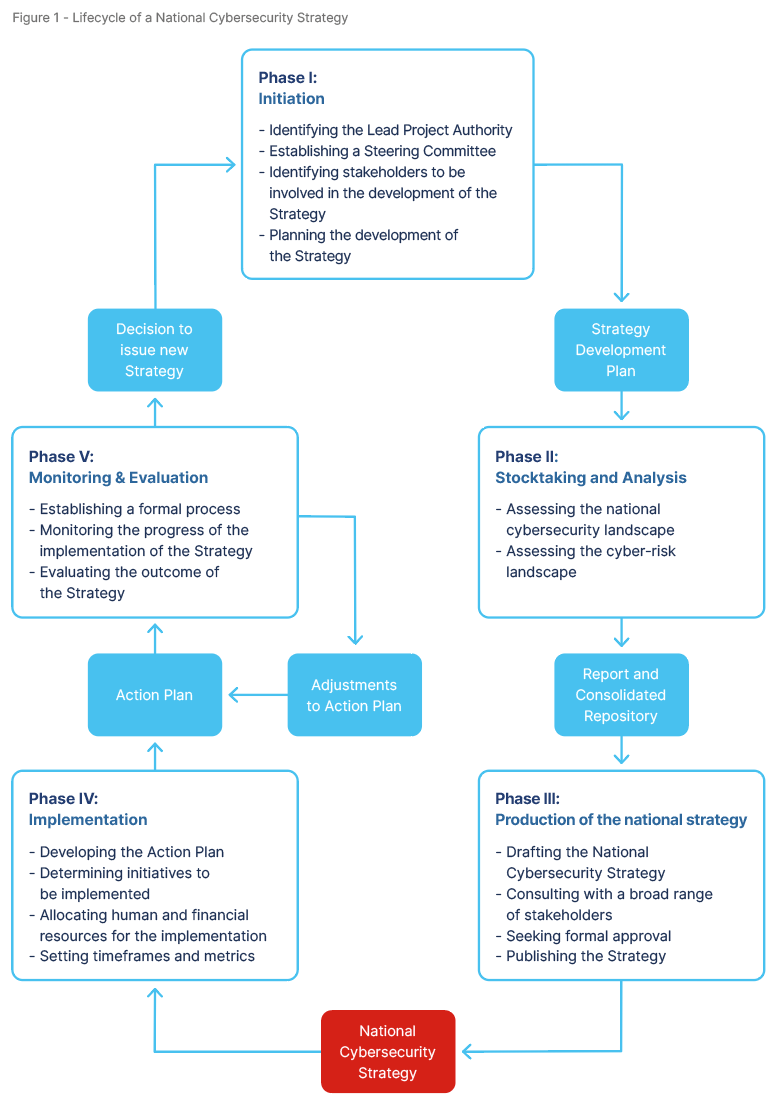

The market currently lacks an extensive knowledge base of best practices and recommendations on this topic. However, the "Guide to Developing a National Cybersecurity Strategy” (NCS Guide) outlines robust, structured, replicable, and governable processes for countries seeking clarity and direction. Published for the first time in 2018 and revised in 2021, the guide's strong point is that it represents a community effort involving tens of experts from different organisations and geographies. These experts gathered together and compiled a guide using a consensus-based approach, resulting in a comprehensive compilation of tried-and-tested best practices that policymakers can adapt to their specific contexts and replicate.

The International Telecommunication Union and the World Bank are currently facilitating a group of experts (of which Experirē is a proud member as well) to produce a new edition of the guide, which should be presented late 2025/early 2026.

The guide serves as a great starting point, and we strongly encourage concerned stakeholders to consult it (it is freely available online).

When things go wrong: from bad to worse practices in drafting an NCS

While resources like the NCS Guide help identify good practices, a decade of experience delivering projects in the strategy domain has taught us that there are also many bad – sometimes very bad – practices.

Strategies are often seen as political documents, rather than valuable blueprints tailored to specific needs. When this happens, NCSs become mere “cybermaturity elevators”, designed to help move their country up in international rankings like the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) or increase the maturity score after an unsatisfactory national assessment. Or simply because “everyone else has it”.

When this happens, the strategy becomes void of any form of commitment. They serve as “placeholder documents” until the next one is published. They have no real substance and represent a waste of resources for the country.

Another issue arises when insufficient stakeholders are invited to participate in the NCS development process. Of course, it will be impossible to involve every single segment of society, and the job of balancing this out rests on the shoulders of policymakers. However, listening to as many stakeholders as possible remains a foundational principle. Policymakers – who usually take the final decisions regarding the strategy – have to essentially hedge their bets about what strategic directive will be most effective. Collecting more information from a diverse set of stakeholders minimises the risk of betting on the wrong horse (while ensuring the additional value of stakeholder collaboration that we already mentioned in a previous section).

Countries sometimes completely outsource the process of NCS creation to external parties, such as consulting firms. While support from these entities is certainly needed (they have the experience and the perspective on what different countries are doing, as well as insight into the challenges of drafting a strategy), the content of the NCS should not be left solely to them. External parties can be involved to facilitate the work, consulting national leaders, facilitating workshops with stakeholders, formalising findings, proposing solutions, and preparing documentation. However, national leaders are the only ones who can understand what is needed. Thus, they should sit firmly at the steering wheel, directing the work and taking accountability.

How to improve national strategic thinking: looking forward with Strategic Foresight

While the NCS Guide, mentioned in the previous section, gives a structured process, the selection of specific approaches and tools is not explored. This leads policymakers to be unaware of existing practices they can leverage to make the strategy more precise and future-proof, such as in the case of Strategic Foresight, a discipline specifically created for future-proofing.

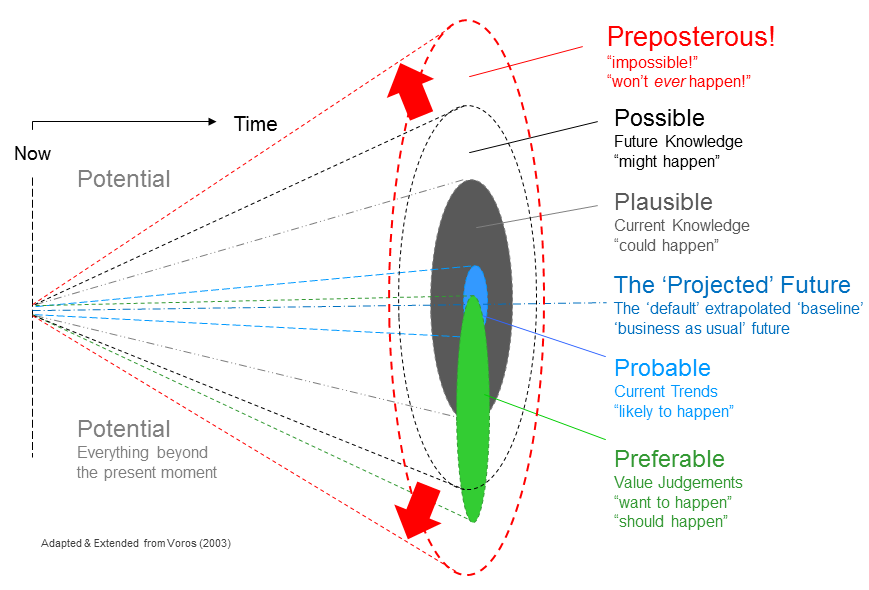

Strategic Foresight relies on systematic processes to explore, prepare, and anticipate future challenges and opportunities. It combines creative thinking and analytical methods to develop a comprehensive understanding of potential scenarios, enabling decision-makers to create or adapt their strategies in the face of uncertainty and complexity.

Strategic Foresight is not merely speculative; it is grounded in rigorous methodologies that have been developed since the postwar period. Today, the toolbox of strategic foresight encompasses tens of methods, approaches, and techniques. Each one has its use, but some, such as Backcasting, Visioning, the Futures Wheel, and the 2x2 Matrix, fit nicely within the context of an NCS project, even if the involved stakeholders are not familiar with them.

Unfortunately, Strategic Foresight is still not common due to a scarcity of experts. This approach usually remains within the confines of higher-maturity countries. At Experirē, we fundamentally disagree, and we are convinced that every country should have access to this capability. That is why over the years we have invested in it, equipping Experirē with in-house expertise and developing connections with a network of top-level foresight experts. We are always ready to present this to interested stakeholders. Reach out if interested (info@experiree.com).